Relation de Chasles

Fondamental : Relation de Chasles

Soient \(I\) un intervalle, \(a\), \(b\) et \(c\) trois réels de \(I\) et \(f\) un fonction continue sur \(I\).

Alors \(\displaystyle\int_a^b f(x)~\mathrm dx=\displaystyle \int_a^c f(x)~\mathrm dx+\displaystyle \int_c^b f(x)~\mathrm dx\)

Complément : Démonstration

Si \(F\) est une primitive de \(f\) sur \(I\), alors :

\(\displaystyle \int_a^c f(x)~\mathrm dx+\int_c^b f(x)~\mathrm dx=F(c)-F(a)+F(b)-F(c)=F(b)-F(a)=\int_a^b f(x)~\mathrm dx\)

Exemple :

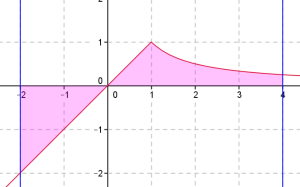

La relation de Chasles permet d'écrire \(\displaystyle \int_{-2}^4 f(x)~\mathrm dx=\int_{-2}^1 f(x)~\mathrm dx+\int_{1}^4 f(x)~\mathrm dx\).

Calculons \(\displaystyle \int_{-2}^1 x~\mathrm dx\) :

\(F_1(x)=\dfrac{x^2}{2}\) est une primitive de cette première fonction. On a :

\(F_1(-2)=\dfrac{(-2)^2}{2}=2\)

\(F_1(1)=\dfrac{1^2}{2}=0,5\)

donc \(\displaystyle \int_{-2}^1 f(x)~\mathrm dx=F_1(1)-F_1(-2)=-1,5\).

Calculons \(\displaystyle \int_{1}^4 \dfrac{1}{x}~\mathrm dx\) :

\(F_2(x)=\ln x\) est une primitive de cette seconde fonction. On a :

\(F_2(1)=\ln 1=0\)

\(F_2(4)=\ln 4\)

donc \(\displaystyle \int_{1}^4 f(x)~\mathrm dx=F_2(4)-F_2(1)=\ln 4\).

Par conséquent l'intégrale cherchée est la somme des deux intégrales que nous avons calculées.

\(\displaystyle \int_{-2}^4 f(x)~\mathrm dx=\int_{-2}^1 f(x)~\mathrm dx+\int_{1}^4 f(x)~\mathrm dx=-1,5+\ln 4\).

Pour l'aire du domaine, il faut compter \(\displaystyle \int_{-2}^4 f(x)~\mathrm dx=\int_{-2}^0 f(x)~\mathrm dx+\int_{0}^1 f(x)~\mathrm dx+\int_{1}^4 f(x)~\mathrm dx\).

On trouve ainsi que l'aire vaut \(\frac 52+ln(4)\).

Complément :

En utilisant la relation de Chasles ou la définition avec les primitives, on peut remarquer que pour tous \(a\) et \(b\) et toute fonction \(f\) continue sur \([a ;b]\), on a :

\(\displaystyle \int_b^a f(x)~\mathrm dx=-\displaystyle \int_a^b f(x)~\mathrm dx\)